Monroe Engel, who had a summer home on Block Island, went to Mississippi in the summer of 1964.

We have joined our Brooklyn family for the last few weeks of summer on Block Island, Rhode Island. This week’s Block Island News features a story of Harvard professor Monroe Engel and his experiences as an older participant in the historic 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer.

* * * * * * * *

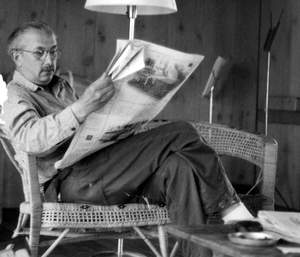

Monroe and Brenda Engel have had a house on the West Side of the island since 1955. Monroe taught English at Harvard University and used his summers on Block Island to recharge and pursue his studies and writing.

Their grandson, Zach Goldhammer, was an intern at The Block Island Times one summer several years ago. He has now graduated from college and is working at The Atlantic Monthly in Washington, DC. While visiting his grandparents this summer, he talked to his grandfather about a summer 50 years ago that was a turning point in the history of this country.

Here is Zach’s account of the role that his grandfather played.

— Fraser Lang

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer, a landmark moment in the civil rights movement that involved a massive African-American voter registration and education campaign and pulled together a coalition of activists from all across the country.

The media has published many stories celebrating various iconic groups which participated in the movement. Portrayals of the activists who moved to Mississippi that summer, however, tend to focus on young, idealistic college students, who headed south to show solidarity in the fight against Jim Crow.

The story less often told is that of the older generation that also participated in Freedom Summer. This is the story that belongs to my grandfather, Monroe Engel, who was in his mid-forties at the time that he went down to Mississippi in 1964. At the time, Monroe (who prefers us to call him by his first name, rather than any affectionate grandfatherly nickname), was already a well-established novelist and English professor at Harvard who specialized in the works of Charles Dickens. He had planned to spend the summer of 1964 as he usually did, on Block Island, where he came to spend time with his family and focus on his own writing.

But when a group of his undergraduate students came to tell him about their plans to go to Mississippi, his plans soon changed.

“They came to see me and asked whether I would go down and teach a course at Tougaloo College,” Monroe remembered.

Tougaloo, which at the time was a segregated, all-black college, was one of the sites where Freedom Summer activists would host free classes. The classes were intended to boost literacy in the region and give college students and local teachers a chance to further advance their education.

“I went down because a lot of graduate students [from other universities] were going to go down to Tougaloo to teach different courses there,” Monroe said, “but they couldn’t get any Harvard graduate students to do it.”

So, despite the hostile threat of the Ku Klux Klan and the news of the three young activists who had been killed for their work in organizing Freedom Summer earlier that June, Monroe decided to head down to Mississippi.

There he became a member of a team of Harvard professors who would teach a two-week intensive English literature course at Tougaloo. Monroe initially wanted to teach the works of one of his favorite authors and preferred subjects for academic research, such as Charles Dickens, but his prospective students weren’t interested. Instead, they requested to read the works of an author whose writing was more relevant to issues of race relations in the American south: William Faulkner.

Though Monroe was not a Faulkner specialist, he decided that he would teach “Light in August,” an extremely difficult novel first published in 1932, whose themes of race and sex in Mississippi remained controversial even three decades after the book’s first appearance. Beyond its difficult structure and controversial themes, teaching the book also presented a logistical problem due to the fact that it was not available in any of the book stores near Tougaloo.

Still, Monroe was resourceful and used his own connections to get around the problem at hand.

“I called someone at Random House, and he agreed to meet the plane I was coming down on, which had a stop in New York, and he’d give a case of the Modern Library edition of ‘Light in August,’ and that I could arrange to have it picked up. I said I’ll make the books available and see if some of them can get to it.”

Once the delivery was arranged, Monroe began teaching his first class at Tougaloo, where he was joined by professor Alan Lebowitz, who taught Ernest Hemingway’s “For Whom The Bell Tolls” and Franz Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis,” and Bill Alfred, who taught Shakespeare’s “King Lear.”

The two-week course quickly proved to be overly ambitious. The college classroom was filled with students and teachers who still struggled with the difficult material at hand. Many found that they didn’t know the vocabulary being used in the books and had trouble making it through the opening chapters.

After the first days class, Monroe decided he would switch over to an oral teaching style, and would have the class read the chapters aloud, so that the students wouldn’t have to struggle with the material on their own. This tactic improved things somewhat, but Monroe will also be the first to tell you that the classes were not a success in and of themselves, and the Harvard professors did not do much to alter the academic challenges faced by Mississippi schools in 1964.

The more important experiences, ultimately, came from interpersonal connections and friendships that were formed outside the classroom. One such friendship lasted long after the professors left Mississippi. Marion, a student of Monroe’s, remembered the Freedom Summer classes of 1964 as “the most exciting time of my life.” The classes inspired him to move to Cambridge in the fall, where he arrived with “seventeen dollars and three telephone numbers, Alan [Lebowitz]’s, Bill Alfred’s, and Monroe Engel’s.”[Marion later enrolled at Harvard with Alan Lebowitz’s help.

For Monroe, the trip also allowed him to see some of the most important civil rights leaders of the decade in person, including Martin Luther King, who spoke at a local church near where Monroe was teaching. While Monroe was impressed by King, he was even more excited by King’s contemporary, Bob Moses, who at the time was a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) leader working on the state’s African-American voter-registration drives. [Moses would later start the Algebra Project, an innovative mathematics education program which applied the lessons that Moses learned through community organizing during Freedom Summer to the problem of making education relevant to students].

For Monroe, the stories of Freedom Summer have become an integral part of his life, and are among the tales he tells most frequently, along with stories of his days as a soldier in World War II and his stories of the old days of Block Island. To hear him recount these stories can make one realize the ways in which a range of worlds have been connected through the work of one man. Though Block Island today may seem worlds away from Tougaloo, Mississippi in 1964, my grandfather’s story remains a living link between these distant and divided spaces.

I was in Clarksdale that summer, registering black voters, and sleeping in a house in the black district. One day I was driving a pickup with boxes of registration materials with a black student from B.U. Another truck pulled up beside us and I looked over to see a shotgun pointing out the window. I jammed on the brakes and the Klan guys missed us. We were terrified. I turned around and floored it back to our house. It was decided that we were a known target and should go back to the SNCC office in Atlanta. I took a bus back to Toronto, and he went to Boston. We had done well up to then.