I’m on Substack now.

You can continue to receive periodic posts for free. Or you can read every post and comment for $5 a month, $60 a year.

I’m on Substack now.

You can continue to receive periodic posts for free. Or you can read every post and comment for $5 a month, $60 a year.

The Illinois Policy Institute, one of our state’s most influential sources for disinformation on taxes, pensions and unions, has come out with their latest talking point about teacher and public pensions.

The IPI claims that 40 cents of every education dollar goes to pensions.

Don’t underestimate the power of an IPI lie. The IPI had a major role in defeating the fair tax amendment to the Illinois constitution last November by spreading lies that even my teacher colleagues believed.

In order to make the claim that 40 cents of every education dollar the IPI had to invent a new definition of the education budget.

The legislature doesn’t consider their pension obligations and education to be in the same category or budget line.

That is an IPI invention.

It would be like claiming that 40 cents of every education dollar in the state budget was spent on healthcare since roughly the same amount is budgeted to both healthcare and pensions.

That would be a lie too.

$1.18 billion went for normal costs (the costs related to paying the actual benefit). It amounted to 20% of the pension budget. 80% ($4.6 billion) went to pay for the debt on the unfunded liability.

Decades of pension holidays, where the state paid nothing of their pension obligations, and shorted payments where the state paid an imaginary statutory number, has created a budget that is out of whack.

When funding our public pensions, what is the difference between paying the statutory amount and the actuarial amount?

This is an important question when discussing the huge Illinois pension liability of over $140 billion because it goes to the heart of how we got here.

The statutory amount sometimes paid by the Illinois legislature to our pension fund is a number based on nothing more than what the politicians decide on.

The actuarial payment would be decided by actuaries that calculate the amount the state must pay if it is to cover its pension expenses.

Actuaries take into consideration an employee’s salary, the number of years they have until they retire and start receiving benefits, the annual rate at which the employee’s salary increases, the percentage of the final salary the employee will receive on a yearly basis when they retire, and the probable number of the years the individual will live to continue receiving those annual payments. Any cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) are also built into the equation.

For the statutory amount politicians just pick a number.

Some years the legislature didn’t even pay the statutory amount.

The words they used to describe what they did those years was taking a “pension holiday”.

Over the decades the practice of taking pension holidays and paying only the statutory amount into the pension funds got us to the point where we have a $140 billion state pension liability.

Yesterday when I was at a luncheon with local legislators and a local chapter of the Illinois Retired Teachers Association, a state senator got up and announced how proud she was that the most recent budget “fully funded the pension systems”.

This was also reported at the time by the Chicago Tribune.

The spending plan also would pay off a $2 billion emergency loan the state took out from the Federal Reserve in December and meet the state’s obligations to fund schools and make its required annual contribution to its severely underfunded pension plans.

But the statutory payment was two billion short of the actuarial number.

The underfunding continues.

And, no senator. You didn’t fully fund our pensions.

The state’s pension liability continues to grow because the Democrats in the legislature continue to short its actuarial payments year after year.

They might want to take a look at Mayor Lightfoot’s budget.

Of course, like most public officials, Lightfoot complains about “unsustainable COLA costs.” But she knows there are limited options for her besides complaining.

The state of Illinois only pays what is called a statutorial amount to the pension funds. That is a number that they pull out of thin air. The actuarial amount is what it will actually cost to pay employee pensions according to actuaries who count what it will really cost.

That is better than the legislature once did when they skipped payments altogether.

But the only thing Cahill can come up with is to change the language in the state’s constitution that guarantees that the retirement benefits earned through a life-time of work cannot be reduced or changed.

Cahill didn’t come up with this idea by himself. We’ve heard it before. It won’t work since those currently in the system cannot have their pension contracts retroactively changed even if the constitutional language was removed.

Cahill says he asked the Mayor why she doesn’t support a constitutional language change.

Well, here’s what Lightfoot said when I asked if she would back a constitutional amendment eliminating or altering the clause:

“I don’t favor that,” she said, adding that state pension plans are contracts that must be honored.

True enough.

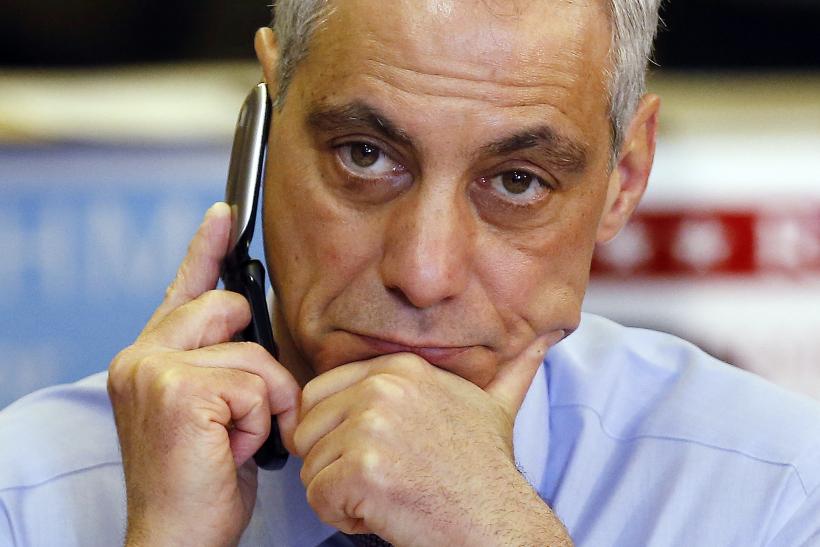

Why is our former mayor even being considered for ambassador to Japan?

Maybe because Chicago teachers’ pension money flowed to financial companies connected to some of the mayor’s friends and top donors while he was in office.

In a 2015 story in International Business Times reported: “When Mayor Emanuel took office, he said he was going to stop the culture of pay-to-play,” said Alderman Scott Waguespack, who is among a group of lawmakers asking the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to investigate whether the donations also violated that agency’s anti-corruption rule. “This is an example of his failure to follow through on those promises.”

Read the entire IBT story here.

The lack of transparency of teacher pension funds and their investors, fees, returns is not limited to Rahm’s relationship to the CTPF.

The Illinois Teacher Retirement System fired all five of its top executives. Only an investigation of CIO Jay Singh and financial officer Janna Bergscheider by the Governor’s Inspector General has been made public.

We still don’t know the details of TRS executive director Richard Ingrams departure over a year ago.

“A drop in the bucket,” someone wrote me in response to Chicago’s Mayor Lightfoot budget proposal of a $31.5 million pool to provide $500 a month to 5,000 COVID-affected low-income families for one year.

“I agree. But this will be the biggest plan for a guaranteed direct cash payment to poor folks in the country,” I said.

And that’s really the point.

Mayor Lightfoot has signed on to the concept of a guaranteed income even if it’s baby steps.

The program would provide relief for Chicago’s poorest families.

A direct cash payment of $500 a month makes a real difference to people trying to make the rent and put food on the table.

The idea of a universal basic income is one whose time has come. Past due, really.

It should be a national program.

Some members of the Chicago city council have claimed the Mayor has “plagiarized” the idea or has “copied” it.

That is just typical Chicago politics and doesn’t matter much as long as the alders pass it as part of the budget.

By Nydia Velázquez who represents the 7th District of New York and is chairwoman of the Small Business Committee. Jesús “Chuy” García represents my 4th District of Illinois and a member of the House Financial Services Committee.

Imagine after years of devoted public service work, your hard-earned pension benefits are now on the brink of being slashed, even when your elected representatives are trying to protect them through law. That is exactly what’s at stake for Puerto Rico’s public sector pensioners.

Earlier this summer, the Puerto Rico Financial Oversight and Management Board, otherwise known as “the Board” sued members of the government of Puerto Rico. The lawsuit attempts to invalidate a new local law — the Dignified Retirement Act — designed to protect pension-holders and essential services in the debt restructuring deal being considered in court. The Board, in taking this action, is violating the spirit of the power-sharing arrangement we established through federal law.

When Congress created the Board through the 2016 law known as PROMESA, it did not give it a carte blanche. Specifically, Congress recognized that provisions of the bankruptcy code incorporated into PROMESA cannot be used to infringe upon the exclusive powers of the local government to legislate. That’s why recent actions taken by the Board in an attempt to force pension cuts in spite of opposition from the elected government are so concerning.

The Puerto Rican government is well within its rights under PROMESA to oppose a restructuring plan proposed by the Board, and to articulate how it believes its debt should be restructured — a decision that will impact Puerto Rico for generations. The government did just that through the unanimously passed Dignified Retirement Act.

Under PROMESA, the legal framework necessary for implementing a restructuring plan must be in place before it can be confirmed by a judge. Therefore, the local government must pass the necessary legislation before the plan can be implemented. Congress specifically sought local input when designing this power-sharing arrangement and decided that the elected Puerto Rican government must maintain its exclusive power to legislate — including in the context of the debt restructuring process.

The Dignified Retirement Act describes the conditions that must be met in order for the government of Puerto Rico to cooperate in the implementation of a debt restructuring plan, including providing for full payment of government pensions and protection of essential government services. The Board, on the other hand, continues to advocate for a debt restructuring plan that would impose an 8.5% cut on any pension payment exceeding $1,500 per month received by retired public servants.

While the press has given much attention to the Dignified Retirement Act, the Board may very well face an insurmountable obstacle to getting its current debt restructuring plan confirmed and implemented. The Board needs the Puerto Rican government to enact legislation to implement the plan, and the government has made clear that it will not advance the implementation of a restructuring plan that would cut pensions and jeopardize essential services.

We urge all parties to arrive at a fair resolution that protects the vulnerable retirees who are facing a cut to their benefits. The Board is not Puerto Rico’s appointed governor or legislature, and it must work with the local legislature to arrive at a mutually agreed resolution instead of putting retirees at risk.

Take a few minutes to read this article in The Intercepts which describes how our pension funds are being used by companies owned by private equity firms in order to fight unions.

Which begs the question as to what voice do we as members of pension funds like the Illinois Teacher Retirement System have in the management of the system’s investments?

To be clear, of the sources of pension fund revenue, teacher contributions and returns on investment have been the most reliable.

The state has been the least reliable.

They continue to short their pension responsibilities by billions of dollars every year.

I’ve been writing about the threats to our teacher pensions for years.

I have spent that time organizing to preserve them.

I was on the phone the other night with a friend who retired a year ago.

“Thank goodness for all those bus trips to Springfield,” he told me.

Many of my retired friends lost interest once the Illinois Supreme Court declared that our pensions could not be diminished or impaired – to use the language of the state constitution.

Once our monthly checks were secured by the Illinois Supreme Court many of us have moved on to other things.

An interesting side bar:

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) is a federal law that requires investors for private pensions to act in the interest of the individuals in these plans.

ERISA does not apply to public pension plans. When some members of public pensions like TRS brought suit to have ERISA cover our public pension plans, the US Supreme Court ruled that they had no standing.

They and we are in a defined benefit pension plan.

In other words, those who manage our retirement savings can do it in secret, can charge hidden fees, can hide actual earnings, but since our monthly pension check is guaranteed, we cannot claim that we are harmed.

In her dissent, Justice Sotomayor wrote, “After today’s decision, about 35 million people with defined-benefit plans will be vulnerable to fiduciary misconduct.”

If, like me, you believe that even though we are retired we are still part of a movement for workers’ rights and social justice, then the idea that our pension funds are being secretly invested in private equity companies to bust unions, is outrageous.

But much of that information is hidden from us by TRS trustees and investment managers.

A monthly guaranteed defined benefit can’t be enough to shut us up.

We have standing no matter what the courts say.

In a blog post by my retired colleague John Dillon, written in 2019, John gave us some of the history of our teacher pension’s 3% compounded yearly benefit increase.

He began by quoting former TRS trustee Bob Lyons:

As past Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System Trustee Bob Lyons observed, “In the 21 years from 1969 through 1989 there was only one year that inflation was less than 3.3% and the average annual rate of inflation was just over 6.2%. In making the decision in 1989 to change our annual increase from three percent simple to three percent compounded, the members of the General Assembly made what they felt was a reasonable assumption that inflation would continue and that it would grow at the rate that it had been for more than 20 years. Since state pensions had not kept up with inflation they would provide a necessary increase, but they did not ask anyone to pay for it because they assumed it would not really be expensive. The change would cost the state, but they assumed it would still run behind inflation. And growing inflation would mean the state would collect more tax revenue.”

Anticipating further elevated inflation rates, the General Assembly granted a change from 3% simple to 3% compounded COLA in 1989 to the retirees in TRS.

Since 1990, (high of 4.1% in 2007 and low of .1 in 2008) the average inflation rate for the country has been overall 2.4%. As Mr. Lyons writes, “The reality is that the change from 3% simple to 3% compounded did just what it was supposed to do and it has more than protected us from inflation.”

And he’s right. On average, thus far, we are looking back nearly 30 years with a .6% positive break. And in our current media environment of people turning on each other rather than to each other, this COLA correction seems unacceptable to those who criticize the Illinois “Pension Problem” as simply an issue of too many benefits. The finger pointing by the Tribune and other anti-union organizations ignore the truth: the cost of pension would not be so overwhelming if there were no debt payment as a result of decades of avoiding payments.

Again, It is important to note that our TRS pension is fixed. It does not change from year to year regardless of any change in the Consumer Price Index or other measures of inflation.

This is not true of Social Security, which teachers do not receive and can vary based on changes in the CPI.

In 2022 it is expected that the Social Security benefit may go up by as much as 5%.

Our teacher pension monthly payment will go up by the same amount it has gone up for two decades. There will be no change.

There is a myth that retirees’ living costs go down. We no longer have to pay the cost of working and working has definite expenses.

The truth is that the government’s official CPI fails to keep seniors on a par with the inflation we actually experience.

The cost of goods, including prescription drugs, housing, health insurance, food, and various taxes go up for the elderly.

Even for those receiving a Social Security benefit have lost 33% of their buying power since 2000.

Among the 10 fastest-growing costs cited in the a survey of retirees were prescription drugs, homeowners insurance and property taxes, several food items, and Medicare premiums.

It is true that some retired seniors own their own homes and are are protected from the rising cost of housing – to the extent that they have fixed-rate mortgages or own their homes outright – but are still are subject to rising costs of property taxes, insurance, and maintenance.

Many retirees are exposed to the volatility of rental rates, which have been on a tear in recent years and show no signs of abating.

I have written extensively on the health care costs that Medicare does not cover such as dental, hearing and vision.

And yet our pension benefit adjustment remains unchanged from year to year.